This blog delves into some NZ based research to discover what compromises are made to adequately ventilate a home, and the risks of not doing so. Effecting a balance is key for health, comfort and reducing energy consumption.

A brief history of ventilation & thermal comfort in NZ

Historically, houses in NZ were built to ‘breathe’. They were so leaky that sufficient cold air seeped in to meet the needs of occupants, and ensure homes had no moisture damage due to the constant breeze. It is comparable to breathing through your skin, not your nose.

I recall the first house I owned, an old weatherboard villa. It had the very corners of the glass panels in the big bay windows deliberately cut out to let the house ‘breathe’…..needless to say it was freezing in the winter and any heating flew straight out! My asthma was not great, I often wore a coat indoors, and I sneezed my way through spring!

This old technique meant that cold winter air would have needed to be warmed to provide a healthy indoor environment, and there was also the issue of managing hot and humid air entering in the summer.

The problem with current ventilation approaches

The air leakages in buildings have been improved, and certainly deliberate gaps are no longer used. However, research and building concerns such as leaky homes have raised issues with how we build and use buildings day to day, in terms of air quality, moisture damage and energy use.

-

Air Movement Through Building Fabric

Even with air leakage occurring in a non-airtight building, the quality of the air coming in through the building envelope will still contain a level of contaminants as the envelope itself is serving as the air filter. This means any chemicals or mould spores trapped inside the wall assembly, or allergens from outside can easily find their way into the home.

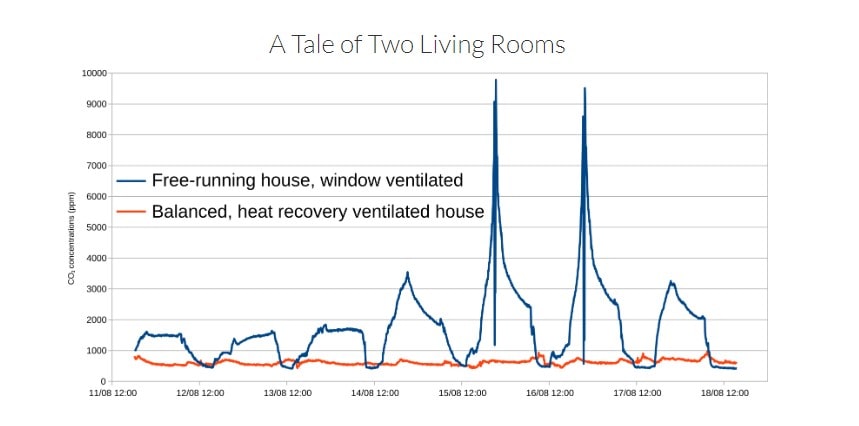

A study1 of two identical houses monitored the CO2 levels, one was ventilated free flow (using windows to ventilate) and the other had a balanced mechanical heat recovery ventilation system. In the graph below, the latter never exceeds the 1,000ppm threshold and is consistent, as opposed to the strongly fluctuating free flow home which exceeds the recommended threshold at its peaks.

Below Graph1: Monitoring of CO2 levels in 2 new 3-bedroom houses in Auckland over a week in winter. Both houses were inhabited by 4 people and a pet.

2. Air Quality from Free Flow ventilation (Opening Windows)

Recent NZ based research demonstrates that relying solely on natural forces (such as opening windows) for the provision of healthy homes in NZ climates is generally poor. The research concluded that the way houses are ventilated is crucial for the quality of the indoor environment2.

Excessive humidity and moisture build up are also cause for concern and even dust mite levels have been linked to the water vapour content in the air.

Without mechanical help the wind is the main driver for air exchange, but wind is not steady and the air exchange unpredictable at any one time. A constant pressure is required to control what is happening3.

3. Thermal Comfort from Free Flow Ventilation (Opening Windows)

Opening windows to create natural ventilation pathways (free flow) reduces thermal comfort and can worsen health problems due to the need for additional heating. While ventilation is essential for maintaining indoor air quality, studies have shown that in current housing stock, it is closely linked to increased energy consumption2.

In Rosemeiers study2, Benziger (1979) defined thermal comfort as ‘a state in which there are no driving impulses to correct the environment by behaviour’. In the absence of thermal comfort stress symptoms surface with associated negative health effects.

4. Improving Air Tightness Without Considering Ventilation

Creating a tighter building envelope to reduce draughts and heat loss, can lead to the growing issue of trapped moisture and compromised air quality. The trapped moisture can damage the building’s structure over time, while poor air quality has been linked to various health issues.

The Solution

Fortunately, there’s a solution when building that addresses both air quality and interior comfort while also reducing heating and cooling needs: Air tightness, combined with insulation and Mechanical Heat Recovery Ventilation (MHRV).

Uncontrolled air movement can be removed once the home is airtight. When airtight the MHRV can work most effectively to control all air movement and air quality within the home.

These principles can be seamlessly integrated into your design, along with other design and material choices, to further enhance performance.

Rosemeier’s study2 supports this approach. It found that a well-designed forced ventilation system, coupled with an airtight building envelope, effectively reduces indoor air contaminants to safe levels. It concluded that an efficient heat recovery ventilation system emerged as the optimal choice, improving both indoor air quality and thermal comfort, and, when considering all factors, was also cost effective.

2Source: Healthy and affordable housing in New Zealand: the role of ventilation Rosemeier, Kara, University of Auckland